Every individual tree has its own character, distinct from every other tree. Many trees together however, are more than just a collection of individual trees. Together they express a different identity, one that individually they cannot have — that of a forest. It is their shared characteristics which creates the nature of the forest. And it is this similarity, heightened by their union, and in which our perception of their individuality is diminished, that prompts us to get lost amongst them; to loose our points of reference within their collective identity.

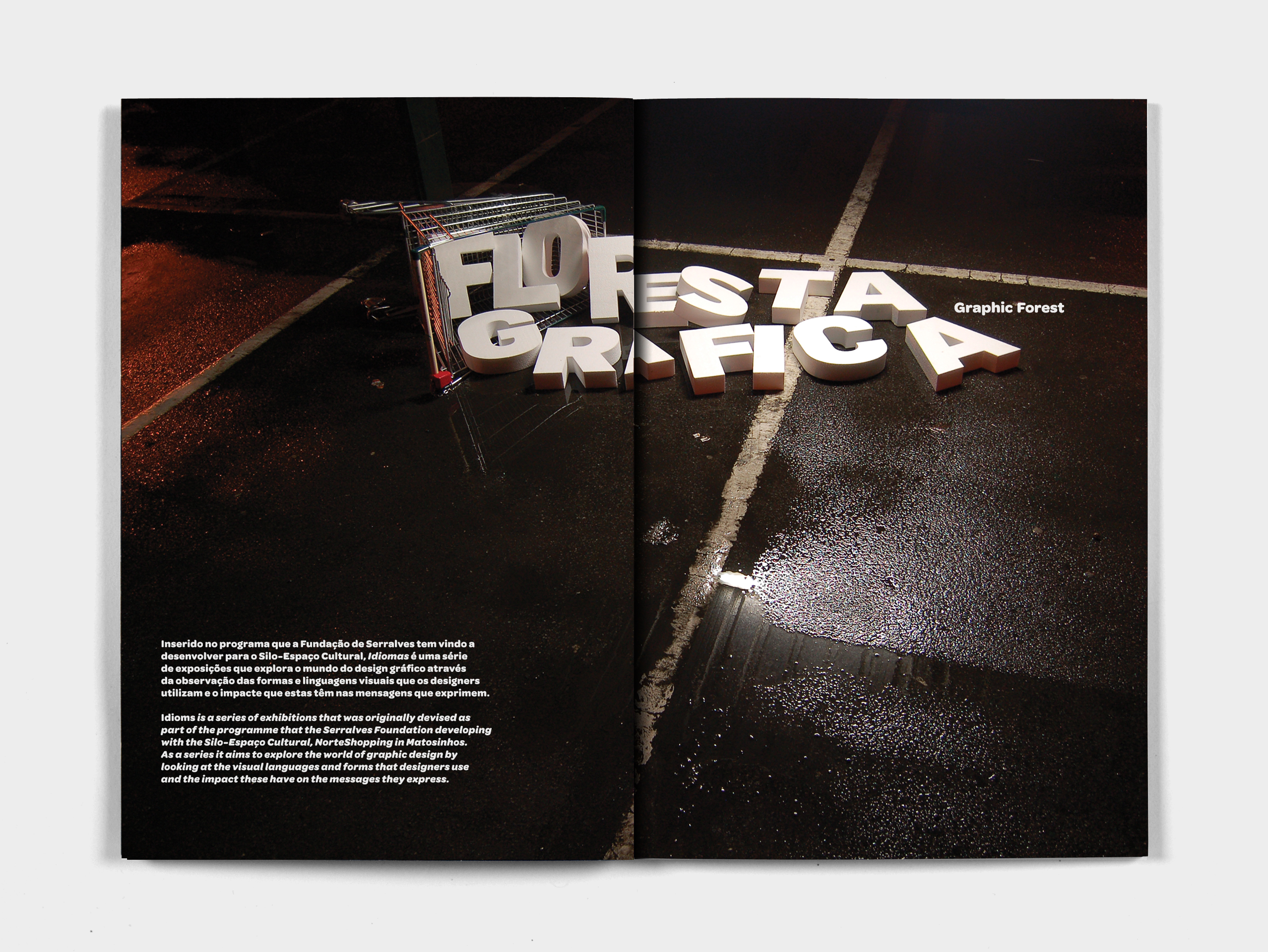

A visit to any large supermarket is testimony to the omnipresence of graphic design in our daily lives. Thousands of products in carefully designed containers, competing for our attention through their visual presentation. And when we consider all the other items with which we come into regular contact — from newspapers, books and magazines to junk mail and wrapping paper, all of which have passed through the hands of a graphic designer — we are able to build a picture of the graphic forest in which we live.

The supermarket panorama is so common to us, so much a part of our daily lives, that it causes us little surprise. In the common course of our routines it’s doubtful that anyone, other than a designer perhaps, would find the time or have the inclination to take stock of the graphic nature of this scenario — to notice that we are in fact standing before a gigantic display of applied graphic design. Although subconsciously we will register the animated type, colours and forms, our most immediate response is normally to see beyond the graphic surfaces as our search focuses instead on the commodities they announce — beans, dog biscuits, bath gel etc. Needless to say, everything on display, from the shape, dimension and material of the containers to the graphic animation of their surfaces, has undergone a careful process of visual styling and presentation — testimony to the industry at work devoted to capturing our attention. So much material that it would fill a building the size of... well, a supermarket!

Unlike the previous exhibitions in the Idioms series, Graphic Forest is closer to being an installation. Its principle focus of attention is not so much the individual design of the materials that surround us — the individual trees, to continue the forest metaphor — but the nature of the vast mosaic that they compose and the messages they send. It’s an invitation to consider the nature of the graphic world that is constructed around us. Whether we want it not, it’s what we’ve got. For the most part, like the majority of things around us we come to accept it as the natural order of things. And, like the majority of things around us, we don’t often stop to consider how much and in what ways our values and expectations are conditioned by these things. Can we imagine a world, a visual environment that is different? Or to put it another way, what sorts of values and priorities does our graphic environment encourage and promote?

This is a debate that has existed within the graphic design profession for many years. It places the concept of social responsibility and ethics on the design agenda. In doing so it asks what this might mean as a guide in determining professional priorities and how the uses and purposes to which designers devote their skills are defined. At various times calls have been issued, in essays, statements and manifestos for a readjustment of priorities within the profession — calls to reject the “high-pitched scream of consumer selling” (First Things First Manifesto, 1964 by Ken Garland) and to devote more time and energy to “more useful and lasting forms of communication”. Together these calls project a view about design as a social tool, part of a collective social project that builds forms of communication that are transparent and that enable and encourage social discourse. This view is confronted by a different understanding; that of design as a service industry with no specific independent aims other than providing a service for whoever should need it. This view of design, its critics claim, places design at the mercy of almost purely economic considerations in which it becomes a tool in the ongoing mission to create and recreate the visual messages and social consciousness on which commodity consumption depends. These differing views result in little common agreement on priorities and core objectives for the profession. Part of the problem lies with commonly perceived limits of professional jurisdiction. These enclose professional practice with the effect of reducing the sorts and the strength of connections that can be made with the larger social and political context that ultimately frames all social practice.

In this reduced context, when confronted with the existence of an item or object there’s a desire (also a natural and worthy human one) to make a good job of designing it. Within the internal logic of design — to make the best possible job of what you’re given — there’s no reason why a packet of cornflakes should receive any less consideration than an art catalogue or health guide. All design projects become equal. That might make sense if the internal logic of design was the controlling logic and communication design was free from ideological burden. It isn’t, in either case. Missing from the equation is the fact that with regard to social analysis, there is little in place within the profession that is able to act as an ethical gatekeeper. In other words, little exists to question the nature of what is ‘given’ before the internal logic kicks in.

There is a conventional belief in designs intrinsic duty to concern itself with the crafting of ‘information’, coupled with an almost noble belief in a sort of ‘neutrality’ or ‘non-interference’ with regard to actual or projected content. In reality, advertising agencies and marketing departments — the leading force in much design work — spend the majority of their time and energy in trying to find ways of imbuing products and services with lifestyle values, relying on the skills of designers in this process.

In buying a particular brand of cornflakes or mobile phone for example, attempts are made to persuade us that we are not simply buying breakfast cereal or a communication device, but that we are buying healthy living or youthful freedom and independence. Most important of all, we are being sold the idea that we can achieve fulfilment, whatever the item and whatever the brand, through the act of purchase and consumption. Even if the exchange was real and true — that beauty, freedom, independence, health, fitness, etc, could be obtained through purchase — the problem remains that the strongest, most dominant value contained in the exchange is that of consumption itself. Consumption and possession as values in themselves, because they draw their power from natural human instincts of survival and self interest, have the capacity to overshadow and outweigh most other values to which they are associated. And that of course is the point of the exchange we are offered.

The most pertinent question that arises from this is not whether some items should be designed well and others not but whether the act of purchase and material accumulation is the most appropriate conduit for the transmission of either individual or collective social values and desires. With this in mind, a notion of social responsibility for designers might entail attempts to separate the transmission of value from commodity production. Not least of all because in creating and modelling languages of communication that aim to do this, designers, voluntarily or not, are drawn into a process of consciousness-forming that inevitably takes them into territory that they often claim lies beyond the limits of their professional concern or interest.

If the search for a design practice linked to social need exists, then sooner or later the process of design has to reconnect to a larger external logic, more deeply rooted in social discourse than the dominant economic imperative can ever be. There has to be a set of reference points that lie beyond the internal logic of design — some sort of guide that can locate the design activity within a collective value system. The graphic forest which is the maze of visual communication we inhabit is not incidental to our world views. Every choice of image, every graphic combination, every visual solution, becomes a way of saying something, a visual language that is part of our cultural dialogue. The nature of this dialogue concerns us all and is too important an issue to be left solely in the hands of those with economic and political power.